A Texas Teen-ager’s Abortion Odyssey

The New Yorker

By Stephania Talarid

June 13, 2022 – full article

A Texas Teen-ager’s Abortion Odyssey

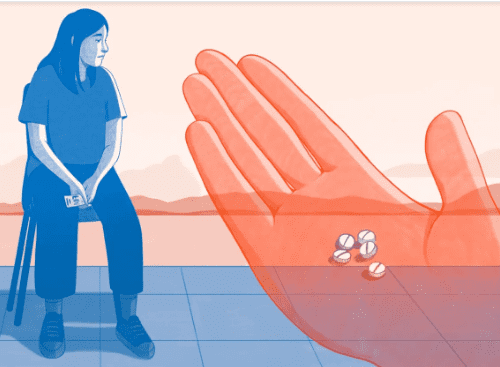

The Heartbeat Act is forcing families to journey to oversubscribed clinics in other states—offering a preview of life in post-Roe America.

Last summer, shortly after a date to Six Flags Over Texas, a thirteen-year-old girl in Dallas was falling in love for the first time. Her father could see it in the pencil drawings she made before bed. Instead of the usual, precise studies of koi fish and wildflowers, she’d sketched herself holding the hand of a boy in a Yankees cap, and enclosed the image in a pink-and-red heart. In the fall, the girl’s father permitted her to meet the boy, a tenth grader, after school one day a week. This spring, when he learned that his daughter was pregnant, he concluded that one day a week had been too many.

Within a day, his daughter, whom I’ll call Laura, came around to the idea that getting an abortion, soon, might be the best option. This required scheduling an appointment with a doctor who could prescribe her one pill to block progesterone and stop the growth of the fetus, and four other pills to prompt contractions. Her father, who worked in a factory painting locomotives on a 4 a.m.-to-2:30 p.m. shift, decided to use his next day off to take her to a doctor to get the medication. The question was: where? Last September, Senate Bill 8—also known as S.B. 8, or the Texas Heartbeat Act—went into effect across the state and sped up the timeline for enacting such a choice. The new law makes it illegal for women to obtain an abortion past the sixth week of gestation, or even before the sixth week, should electrical activity in fetal cells be detected by ultrasound. No exceptions are made for pregnancies that result from rape or incest, or for those of very young teen-agers.

The father’s girlfriend, who is close to Laura and controlled the household supply of sanitary pads, deduced that the girl had missed only one period. That meant Laura might just beat the six-week cutoff, so the girlfriend hastened to call local clinics. A few hours later, though, she and the father were confronting a fact faced by many other Texas families since the passage of S.B. 8. “Everything is booked out for a month’s time, if you can even get someone on the phone,” the girlfriend said. In the nine months since the law was implemented, the number of abortions performed in Texas has fallen by half, according to the Texas Policy Evaluation Project, at the University of Texas. Meanwhile, thousands of women and girls who want to end their pregnancies have been compelled to seek care in other states.

For Laura’s family, the nearest option was Oklahoma, but none of the clinics that the girlfriend called had appointments available. In Arkansas, the wait to see a doctor would be weeks—a delay that the father thought would be hard on Laura, an eighth grader who sometimes spoke of feeling isolated and depressed. “I’m not putting her through that,” the father told his girlfriend. Finally, seven calls later, the girlfriend reached a clinic in Santa Teresa, New Mexico, whose doctor could see Laura that weekend. It was a decent place, the girlfriend could report with confidence; she’d taken a pregnant relative there the month before. There were two catches, though. The clinic was seven hundred miles away, and the cost was, for the family, exorbitant.

Under Texas law, insurers are forbidden to cover abortions unless the woman’s life is at risk. At the New Mexico clinic, the appointment to get a sonogram and obtain the five abortion pills would cost the family seven hundred dollars. And, because the trip was so long—ten or eleven hours by car—they would also have to leave a day early and pay for somewhere to spend the night. The previous month, the father had ransacked his savings to make a five-thousand-dollar down payment on a three-bedroom house—a step up from the decrepit rental where the family had lived for five years. After renting a U-Haul truck for the move, paying utility deposits, and buying pots, pans, and a toaster, all he had left was fifteen hundred dollars—his emergency stash, “something to fall back on,” he said. He felt sick at the thought that he’d now be using that stash to secure a legal abortion for Laura in New Mexico.

The father understood intimately what teen-age parenthood entailed. Laura was born when he was a high-school sophomore. She was, as he always told her, a wanted child. But, after his relationship with Laura’s mother imploded and he found himself raising their daughter and, later, two younger girls, it had taken him a decade, and at times three jobs, to get his family off public assistance. If Laura had a baby, they might find themselves slipping back into the food-stamp life they’d left behind. More than that, though, the pregnancy threatened a particular dream he had for Laura: that she would press through this hard phase of her adolescence childless, and enjoy some of the fun, silliness, and high-school dance parties that he had missed.

One in four girls and women in the United States will, at some point in her life, seek an abortion. Yet, if the Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade, which, in 1973, established a woman’s constitutional right to the procedure, the long journeys to oversubscribed clinics that have become a fact of life in Texas will almost certainly become the norm throughout much of the country. Post-Roe, legal authority will devolve to the states, thirteen of which have in place “trigger laws” that would ban all, or nearly all, abortions. Ultimately, according to the Guttmacher Institute, twenty-six states are likely to outlaw the procedure. Some pregnant people in the U.S. who will be stripped of the right to legal abortion will go on to have illegal procedures. Others will be forced into motherhood. And millions of families will find themselves grappling with the same calculations that Laura’s family was encountering this spring: How far are we able to go, financially and emotionally, to terminate a pregnancy? And, when it’s all done and paid for, how much farther down the socioeconomic ladder will we be?

By necessity, the trip to get Laura an abortion would be a family affair. The father’s girlfriend would come along to be with Laura when she saw the doctor, and Laura’s sisters would also be joining them, the family budget being too tight to cover two days of babysitting. The father told the younger girls, in lieu of an explanation, “This is a top-secret mission.” He hoped they might never learn that Laura had been pregnant. But, in a time of regrets about his parenting judgments, taking his eldest girl out of state to have the abortion would not be one of them. “There’s always a crowd of people outside protesting,” he said, of Texas clinics. “They’ve got baby-fetus signs and are yelling, ‘In the name of the Father!’ They’re coming to your car window as you’re driving in.” Even if Laura had been able to get an appointment for an abortion within the time frame demanded by S.B. 8, he couldn’t stand the thought of subjecting her to the shame and stigma associated with the procedure in his home state.

Instead, one gusty Friday afternoon in April, he, his girlfriend, and the three girls climbed into a blue Chevrolet van and headed west. The middle sister, who was eight, brought along persistent questions—Is Laura sick? And, if she is sick, why does she have to go so far away to see a doctor? The four-year-old brought along her stuffed unicorn, Chelsea. For the journey, she had put on bright-pink sneakers, and they lit up every time she tapped her feet.

The small, unincorporated community of Santa Teresa sits on the southern edge of New Mexico, a short drive from downtown El Paso. A developer established the town in the nineteen-seventies, envisioning a binational planned community of industrial parks, country clubs, and luxurious homes—a dream that, by the nineties, had failed. Today, as its golf courses turn to rubble and the tennis courts grow hairy with weeds, the new draw in town is a clinic tucked away in a drab strip mall near the Rio Grande, where girls and women can end their pregnancies legally.

Women’s Reproductive Clinic, which is poised, post-Roe, to be among the last remaining abortion providers in the Southwest, is situated alongside insurance businesses, fast-food joints, and a cannabis store. Last year, it averaged a hundred and fifty-four abortion patients a month. This spring, thanks to Texas’s new restrictions, the number of monthly patients is nearing three hundred. Occasionally, picketers in front of the clinic try to intercept arriving patients and usher them into a large turquoise van, where free sonograms are performed and anti-abortion literature is shared. But on most days a sense of stillness pervades the outside of the clinic, in part because of Juan Carlos, a spry, silver-haired security guard whose gaze alone is said to dissuade those who may be primed for a fight. The greater tension, since the passage of S.B. 8, lies on the other side of the tinted-glass doors, in the waiting room.

In late April, when I visited the clinic, a receptionist named Elizabeth Hernández sat at a desk heaped with patient records and bills, greeting women and answering calls. Lately, she said, some of the callers are panicked as they schedule appointments, asking, “Am I going to get arrested? Are they going to follow me from the clinic afterwards?” A provision in S.B. 8 allows any private citizen to sue those who “aid or abet” a woman seeking an abortion in Texas past the six-week mark, whether the abettors are Lyft drivers or relatives who lend money for the procedure. Hernández, who is thirty-five, feels the ambient anxiety surrounding S.B. 8 even when she goes home, where her children have started worrying that she’ll be attacked on the job.

read full article here